You Are the Story You Live: Sister Act, Embodied Theology, and the Work of Lent: The Problem with Lent as Checklist

There is a version of Lent that looks like this: give up chocolate, attend an extra service on Wednesdays, maybe read a devotional before bed. Check, check, check. If you’re super holy, you might even consider the ancient practice of alms giving (giving to the poor and feeding the hungry) to your checklist.

By Easter Sunday, the season has been observed but not necessarily inhabited. We have done Lent without, in any deep sense, living it. Please don’t read this as critical but as a call to consider how we might make the most of our sacrifices and offerings.

What we see happening all around us in Lent is the perennial temptation of religious practice: to reduce transformation to performance, to mistake the map for the territory. The prophets of Israel railed against it. Jesus warned his disciples about it. Yet the pull is powerful, because a checklist is manageable and bounded in ways that genuine conversion is not.

Another way to navigate this season is to understand what Lent is asking of us. What it calls us to and who, ultimately, it calls us to be. Lent is not primarily a set of practices to complete. It is a story to step toward inhabiting our whole selves, body and mind and presence and community. As the theologian might say, this is an embodied practice. And one of the most surprising teachers on this subject is a 1992 musical comedy about a lounge singer hiding from the mob in a convent.

As theologian Wendy M. Wright puts it, “The liturgical year roots our faith. It grounds the invisible, animating our lives in the visible, tactile world. It is elemental. It drapes flesh on the skeletons of our too-ghostly religiosity. It connects heaven with earth, divine with human. It allows us to access the mysteries of our faith. In its feasts and fasts we taste and see God.”

What Is Embodied Theology?

Before we get to the nuns (yep, keep reading), it is worth pausing on the phrase "embodied theology." The word theology tends to evoke big ideas or abstractions: doctrines, propositions, arguments about the nature of God. Much of it can be important, rigorous, cerebral work. But Christianity has always insisted, almost scandalously, that God did not remain abstract. God became flesh. God had a body. God ate fish, wept at a grave, felt nails in his hands. And, in doing so, offers us a way to get splinters pickup up our cross and feel the pangs of hunger on a Tuesday in late February.

This is not incidental to Christian faith. It is the center of it. And it carries implications for how we practice that faith. Embodied theology is the recognition that we do not simply believe our way into transformation. We practice our way there. Hence why it makes sense that early Christians called the practice of being Christians and following Jesus “the way”. Our bodies shape our souls, which really, might not be all that separate as we like to imagine. The habits we form in physical space, with physical voices and physical communities, work on us at a level deeper than intellectual assent.

The philosopher James K.A. Smith writes that we are what we love, and that what we love is shaped less by what we think than by what we do: by our liturgies, our rituals, our repeated bodily practices. We become, in a very real sense, the story we perform over and over again. Lent takes this seriously. It does not merely ask us to consider the Passion narrative. It asks us to walk it, to fast, to kneel, to gather in community, to mark our bodies with ash, to sing lament before we sing alleluia.

Which brings us to Deloris Van Cartier.

Sister Act and the Unlikely Conversion

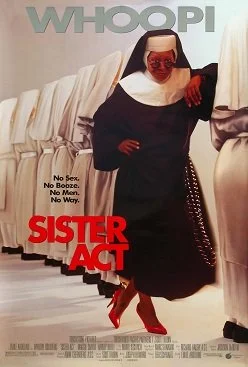

Theatrical release poster

Sister Act (1992) is, on its surface, a comedy. Deloris (Whoopi Goldberg) is a Reno lounge singer who witnesses her mob boss boyfriend commit a murder and is placed in witness protection by a well-meaning but overwhelmed detective. Her hiding place, chosen perhaps by divine irony, is a struggling Catholic convent in the rough neighborhoods of San Francisco. She is given a habit, a new name, Sister Mary Clarence, and strict instructions to blend in.

She does not blend in. At all.

Deloris is loud, irreverent, unimpressed by vespers, and entirely uninterested in the quiet, cloistered life the convent represents. She is, in other words, a person who has not yet been formed by a story larger than herself. She is talented, charming, and fundamentally unmoored.

The turning point of the film comes when Deloris takes over the convent choir. The sisters, under the existing choirmaster, have been a disaster, dutiful but joyless, technically present but spiritually absent. They sing the words without living them. They go through the motions without the motion going through them. Sound familiar?

Deloris transforms the choir not by teaching them to be less religious, but by teaching them to be more present in their words and presence on the stage. To act as one body with a shared song to sing. To be coherent. She insists they feel the music. She drags jazz and gospel and rhythm into the stiff repertoire. She asks them to raise their voices, move their bodies, engage their whole selves in the act of praise. And something extraordinary happens: the choir becomes genuinely good. More than good, they become joyful. The church fills up. The neighborhood responds. The music is no longer a performance of piety; it has become an encounter.

Then… well, if you want to know how it turns out, you’ll just have to watch the film.

The Body Changes the Soul

This is the theological heart of the film, hiding beneath all the comedy. When the sisters begin singing as though the words actually mean something. When they bring their bodies and voices and joy to bear on their practice, they are changed by it. And it begins to change everything around them.

Deloris herself undergoes a conversion she did not plan on. She came to the convent as a refugee. She leaves having found something she did not know she was looking for: belonging, purpose, a community whose life has depth and meaning. She did not arrive at this through a moment of intellectual decision. She arrived at it through practice in the physical act of leading, teaching, singing, living alongside people who were trying, however imperfectly, to embody something true.

This is precisely how Lent is supposed to work.

When we fast, we are not merely skipping meals to demonstrate willpower. We are training our bodies to say that we are not simply animals driven by appetite. Instead, there is something that matters more than the immediate satisfaction of desire. When we give alms, we are not completing a charitable transaction. We are physically practicing the claim that our neighbors' needs are bound up with our own flourishing. When we gather for Stations of the Cross, walking the path of Jesus' suffering in real time and real space, we are not watching a memorial. We are stepping into a story and letting it reshape us from the inside out.

The medium, in Lent, is the message. The practice is the theology.

What Story Are You Living?

At Parable Media, we understand that stories are much that the words you tell. They are even more than the images on a camera or the beautiful moments caught on video. Our call, as ministers of the gospel, are to help you flesh out and share these powerful stories that you live in every day. This is what great stories, like Sister Act, do to us- they transform and challenge.

Through the collision with their new sister and her… unconventional... leadership, the nuns come to learn that there is a difference between wearing a habit and being habituated, between performing holiness and being slowly, joyfully, disruptively formed by it.

This is the Lenten journey at its best. We walk it not to earn anything, not to demonstrate our seriousness, but to be formed. It is to let the story of death and resurrection work its way into our muscles and our habits and our communal life, so that when Easter comes, it is not just a date on the calendar but something we have, in some small way, already begun to live.

The alleluia that waits at the end of Lent is not a reward for successful spiritual performance. It is the song of people who have walked through the dark and found that the story was true all along.

So raise your voice. Mean what you sing. Let the practice do its work.

That is what Lent is for.